In any discussion surrounding vegetarianism or veganism, protein remains a seemingly unavoidable theme. More specifically, the concern is that by abstaining from meat and other animal-based foods, an insufficient intake of protein will negatively affect one’s health. Plants are thought to contain incomplete, lesser-quality protein that will lead to a deficiency.

But let’s be clear: it’s a myth, and a tenacious one at that, which is why one should know how to promptly set the record straight. With this in mind, here is an excerpt from the official position paper of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) regarding vegetarian diets in the broad sense that includes veganism:

“A concern that vegetarians, especially vegans and vegan athletes, may not consume an adequate amount and quality of protein is unsubstantiated. Vegetarian diets that include a variety of plant products provide the same protein quality as diets that include meat. Protein consumed from a variety of plant foods supplies an adequate quantity of essential amino acids when caloric intake is met.“

This assertion reflects our current understanding based on the scientific literature on the topic. The AND, with over 100,000 members, is the most important association of nutrition professionals in the world. In my experience, this one single argument is usually enough to put any doubts to rest when someone stubbornly seeks to perpetuate the myth despite a lack of serious knowledge on the matter.

It is true, however, that plant foods can provide little to none of certain amino acids, the different building blocks that comprise protein. This has led to the idea of protein combination, another widespread belief according to which vegetarians need to combine incomplete protein foods at every meal, which sounds rather complicated on day-to-day basis. Not only has this theory been invalidated by the medical profession, even its original author Frances Moore Lappé has come to refute it. The AND supports this stance in its position paper as well :

“Combining two or more incomplete protein foods is not required in every meal as long as variety is present.“

So in short, as long as it is varied and sufficient in calories, two perfectly reasonable conditions that apply to any diet that claims to be healthy, a plant-based vegan diet comes with no risk of protein deficiency whatsoever. For a slew of reasons, this conclusion actually isn’t all that surprising.

A first clue is that human breast milk contains a meager 0.8% protein, among the lowest of all mammals. If our bodies truly required such high quantities, one would expect this to be reflected in the composition of the liquid that has been fine-tuned throughout evolution to stimulate such a key stage of our growth.

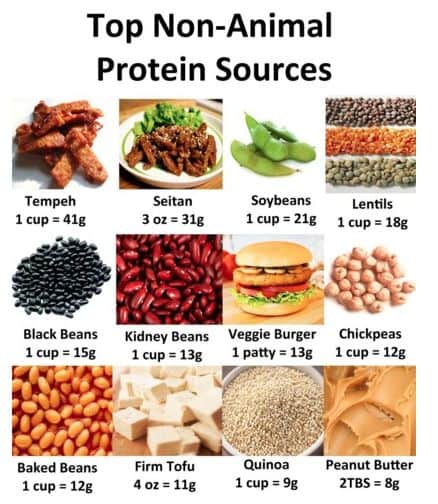

Most people may not even realize that all foods contain protein. Along with carbohydrates and fats, protein is one of the macronutrients that provide the body with most of its energy and can be found in everything we eat in various ratios.

Believe it or not, all protein initially comes from plants. If we’ve dubbed them the essential amino acids, it’s because our organism cannot synthesize them on its own, so we need to obtain them through foods. The same goes for the animal we eat, whose protein was originally in the plants that fed it. Moreover, the largest and strongest land mammals, such as the hippopotamus, the rhinoceros and the elephant, are all herbivores that reached their colossal size by consuming plant matter exclusively.

Although these animals may have digestive systems that are biologically different than our own, the exploits of numerous vegan athletes dispel all doubt. Compelling real-life examples abound : strongman Patrik Baboumian broke his share of records in his discipline, as did Olympians Kendrick Farris and Carl Lewis, and let’s not forget the inspiring transformation of ultra-marathoner Rich Roll.

Strongman Patrik Baboumian

But what about the average Joe? Concretely, authorities agree that the recommended daily intake of protein is 50g for women and 60g for men. Note that this isn’t a bare minimum for good health, but rather an optimal quantity aimed at covering the needs of more than 95% of the population. And yet, according to the statistics of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, average protein consumption per person in developed countries amounts to 103g per day in 2009-2011, more or less double the recommended amount.

This gap may be attributable to the fact that we instinctively associate protein with meat, while perhaps not realizing that, as previously mentioned, all other foods contain protein too. As a result, we unknowingly take in protein in excess. According to a 2013 review of 32 studies on the matter, the long-term effects associated with a high-protein and high-meat diet include disorders of bone and calcium homeostasis, of renal function and of liver function, as well as an increased risk of cancer and a precipitated progression of coronary diseases. This doesn’t entail that meat is poison, but rather that cutting down on animal products is most probably a smart move based on the science.

Let’s not forget that we do not eat isolated nutrients. When considering specific foods, we need to take into account their nutritional package as a whole. Animal protein, while certainly complete, comes bundled with saturated fat, cholesterol and sodium (salt). On the other hand, protein from plant sources brings a heap of positive baggage along with it, such as dietary fiber, vitamins, minerals, antioxidants and phytochemicals (phyto = plants), all of which are beneficial to our health.

Speaking of fiber, most of us aren’t getting enough. Our enthusiasm for meat, eggs and dairy products tends to bump down consumption of fruits and vegetables in developed countries where the average daily intake per person is close to 12g instead of the recommended 30g.

How is dietary fiber important? Despite not having any apparent nutritional value, it serves a pivotal role in optimizing our intestinal transit and fostering the diversity of our gut flora. The study of the microbiome is actually quite relevant at the present time, as scientists are progressively discovering the inner workings of this microbial community inside us and how it affects our health in various ways.

Meanwhile, there is not one single case of protein deficiency in the context of a calorie-adequate diet, but much to our exasperation, this hasn’t stopped the plant-based conversation from revolving around protein.

Luckily, you now have the one and only argument you need to swiftly nip the protein concern in the bud: the largest association of nutrition experts in the world, with over 100,000 members, has examined the balance of available scientific evidence and concluded that, as long as the diet is varied and meets caloric needs (fundamental elements of any healthy eating pattern), protein is a non-issue.

Pin for later:

Sources :

[1] Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Vegetarian Diets (2016)

[2] The composition of human milk.

[3] DG Agriculture and Rural Development based on data from FAO

[4] Adverse Effects Associated with Protein Intake above the Recommended Dietary Allowance for Adults.

[5] The Application of Dietary Fibre in Food Industry: Structural Features, Effects on Health and Definition, Obtaining and Analysis of Dietary Fibre: A Review

Great article – one small clarification – in ruminants significant portion of their protein originated from the bacteria in their digestive system. So all protein originated in plants and bacteria :)

Hi Michael, yes you are right about that. Since the article was already getting quite lengthy, I decided to leave that detail out since their gut bacteria necessarily need the plant foods to produce the protein anyway. Thanks for reading and contributing! ?